The Data Survey Team consisted of a small group of students with a range of high level expertise as surgeons, and technology, marketing and financial executives to leading companies and organizations. The team was charged with developing a new survey platform using new digital tools to produce better data that could in turn improve the quality of life of township residents. As the team wrote in their report,

“If there is an inability to obtain accurate data, then how can businesses, NGOs, and government agencies even begin to address socio-economic issues facing this population?”

The Power of Ethnography

Prior to their arrival in Cape Town, the team developed a desktop research report that outlined what seemed to be a reasonable plan based on their understanding of technology prevalent in the townships and data collection processes. After one week of ethnographic research in the townships interviewing residents, small business people, local representatives, government officials and private companies, they found their desktop research deeply flawed. They were surprised by the proliferation of smartphones and social networking applications such as WhatsApp.

More profoundly, through their field research, the team learned that there was no shortage of data collected or intelligent deployments of technology to amass the data. In fact, township residents had a sophisticated understanding of the value of their data. They knew that it was being turned into a product and sold to private companies, or being used to get more funding to pay for NGO or university salaries. They knew they were not being remunerated fairly; that they were getting the crumbs while someone else was getting the cake.

An even bigger pain point for township residents: the failure of the revolving door of data collectors to improve the quality of their lives. The team heard this frustration loudly and clearly from residents.

- From a local barber, “I’m giving you information, but I still live in a shack.”

- From a small restaurant owner, “I’m filling you up with my data. I’m giving you my food.”

- From a single mom, “I’m sick of filling out surveys and not having the quality of my life improve.”

As the team wrote in their report,

“Most interview subjects realized that their data was being collected, but none of them saw value in it… They did not see any action taken and they realized that sometimes their data was used for the personal gain of others. Fatigue in the answering process is a real issue for a people who have been co-operative in the hopes that it would inspire change.”

One of the largest obstacles was the short lifespan of the data’s relevance given the growth and dynamism of townships. The Cape Town Department of Economic Development and Trade collects census data (considered the “gold-standard” for township data) every 10 years. According to the team’s report, by the time it is processed and released for use, “the information is obsolete.”

Moral Reckoning

By asking the hard questions, the team located the disconnect in the production of high-quality data in the imbalance of power between the data collectors (private companies, NGOs, and government agencies) and owners of the data (the township residents themselves).

By way of getting to this conclusion, the group had to confront the moral ambiguity of their assignment as students of an elite institution culling data from township residents.

“Our approach is a small microcosm of the more prominent ordeal that data collection is facing. Although we had meaningful and thoughtful interactions, the very same people we interviewed called us out on our methodology. To them, we were, ‘just another team.’”

The team’s conclusion,

“...surveying in this complicated situation seems to require an approach just as unique and dynamic as the environment itself…. It brings to surface the need for a viable data set created by the people of the townships for them and managed by them.”

The Aha Moment - Data Stokvels

Searching for a market structure that would give township residents power over their data, the team came up with the idea of “data stokvels,” or what they also called, “ethical data exchanges.” The concept riffs off a popular South African financial instrument called “stokvels.” These are savings-clubs of small groups of individuals. Members contribute financially on a regular basis and the membership, as a whole, benefits. The team explained,

“Traditional stokvels deal in a familiar medium, cash, and whether they are for funerals, savings or grocery, they are in essence a trust. This is part of the reason for their success, the sense of community and obligation to the other members of the stokvel. The second part of the success is the distrust of traditional means of saving, or the banking system. People felt marginalized and ignored because individually they had little bargaining power at a bank, however as the manager of a stokvel, they command respect.”

The data stokvels concept melds this community organizational model with a brokerage system. Leveraging the high quality of the data collected by trusted community members, data stokvels would pool their power to negotiate price, determine access and the scope of queries, and demand accountability. It would give members control over their data - who it’s sold to, what it’s used for, and the price and terms of the sale.

The Team tested the idea of data stokvels with a number of government officials and township residents. In both cases, people’s eyes lit up when they heard the idea. Commenting on their achievement, IE Brown faculty member Meghan Kallman shared,

“I think the team learned a huge amount from deeply engaging with the moral conflict around the business value of data. By asking questions that may have initially felt peripheral to business, they developed a strong project that engaged a very unique business opportunity.”

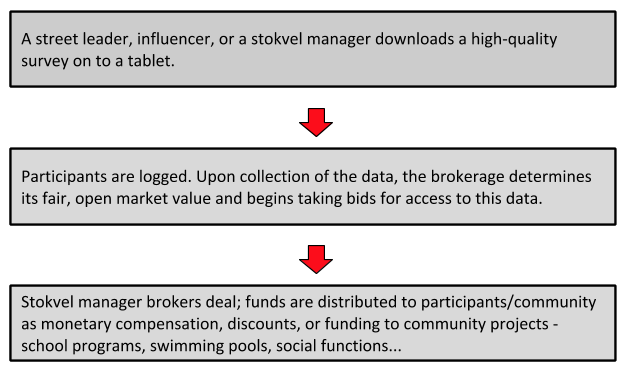

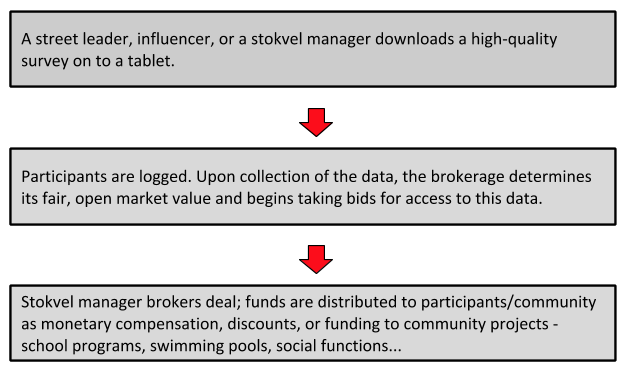

Data Stokvels Process

While many details need to be ironed out, the team outlined some of the major steps of the data stokvels process, summarized below.

Data Rights - Not Just a Township Problem

Data rights is as much an issue for the residents of townships in Cape Town, as it is for individuals operating in digital realms. As we conduct business and our personal lives in an increasingly online world, powerful companies and state-entities are hoovering up our data regardless of our developing or developed country status.

Like township residents, as digital citizens, we do not control collection of our data - who it’s sold to, for what purpose, and in whose interest. And we are certainly not being remunerated proportionately to the revenue that its generating.

By asking the hard questions, mulling in moral ambiguity, the IE Brown 2018 Data Team shed light on opportunities far beyond the townships demonstrating the power of critical and interdisciplinary thinking to uncover innovative business solutions for a global audience and citizenry.

Where Do We Go From Here?

“The environment and the learnings of the program compliment each other very well. Cape Town has historical layers and dynamics that uniquely impact the lives of citizens and businesses. Only through paying careful attention to all the factors - whether they are political, sociological, economic, or others - does a solution become clear and plausible.” EDWIN YU, IE Brown 2018

Though the Team went home and returned to their jobs, this isn’t the end of the data stokvels idea, one still very much in its infancy. Like other projects that successive IE Brown cohorts have developed in Cape Town, the IE Brown class of 2019 will pick up where the current cohort left off and continue to explore the market for data stokvels leveraging the findings, questions, and recommended next steps of the prior class.